|

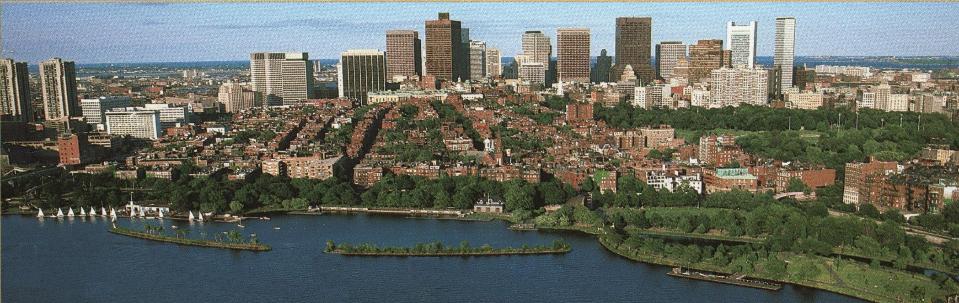

A home away from

home

Somali

Development Center helps refugees forge a new life in Boston

(Boston, January

23,

2008 Ceegaag Online)

Mariam Kaahin Ahmed came home one day in 1991 and found

her husband dead. He wasn't a soldier, but Ahmed suspects he

was killed in one of the many random acts of violence that

plagued Mogadishu as the once-prosperous capital of Somalia,

and the rest of the country, descended into civil war.

Rival groups shelled each other without regard to

civilians, recalled Ahmed, who now lives in Jamaica Plain.

She fled Mogadishu with her four children, aged 3 to 15 at

the time, and for the next few years they wandered from town

to town, trying to go where the war wasn't. The trek took

them to Ethiopia in 1998 and Egypt in 1999, where each time

they stayed with other Somali refugees they knew. In Cairo,

Ahmed applied to immigrate to the United States, citing her

refugee status, was interviewed, and accepted. Her children

decided to stay, she said; today two are in Kenya and two in

Somalia.

Arriving to Boston March 30, 2000, Ahmed already knew

some Somalis she could stay with until finding more

permanent housing. Within a few weeks, she was taking weekly

citizenship classes at the Somali Development Center in

Jamaica Plain that taught English, US history, government,

and civics, and would eventually prepare her for her

citizenship test.

Ahmed doesn't dwell on the past and dismisses her

troubles to "destiny" while crediting her survival to "faith

in God." When asked about her husband, Ahmed lets out a

short, tired laugh and points to a headline in the Metro

newspaper: "Teen shot three times on crowded Orange Line."

"Everybody die. Everybody die," she said.

The display of resignation and resilience has helped many

refugees of the anarchic country adjust to Boston and a

handful of other North American cities that are far

different from the environments they left behind. It is

often a long process, one that involves challenges common to

immigrants, such as language barriers, but also challenges

unique to Somalis, such as learning to live in a governed

society after knowing only either war or the refugee camps

of Ethiopia and Kenya.

"People think once somebody's already here they can

easily assimilate," said Abdirahman Yusuf, who founded the

Somali Development Center in 1996. He estimates 8,000 to

10,000 Somalis have arrived in New England since 1992. Many

of the more recent refugees are Somali Bantu, from the rural

southern part of the country. "For people who have not been

to school and who have lived in small villages from the

country, everything is new," from refrigerators and medicine

to clothing and "just being part of a society where the

majority of the people are of a different race and

religion."

Ceding power to women

Among the issues some Somali families wrestle with is

whether to allow female members to work, Yusuf said. Despite

financial hardship, men are sometimes reluctant to cede

women the power that comes with employment or help with

child care and other household responsibilities.

"Once a woman acquires skills and money, that becomes

power, the roles have shifted, and many men feel

uncomfortable with that," said Yusuf. "But given the right

support and encouragement, many of them want to work; and

they're very good workers."

Many refugees, including women who have undergone female

genital mutilation, take a long time to open up about their

health issues, said Jennifer Abbott, who taught citizenship

and women's health classes at the Somali center. "I waited a

year before talking about anything sensitive or having to do

with reproductive health," Abbott said.

Abbott, who, moved by the plight of the refugees enrolled

in the New England School of Law last fall, also worried

that many Somalis are placed in violent neighborhoods where

hearing gunshots outside their windows is not unusual.

"These people are trying to flee violence, and they

suffer major post-traumatic stress and they have major

flashbacks," said Abbott, 27. "You want to be grateful for

everything they've been given. But at the same time, it's

just not acceptable to put somebody in a situation like

that."

New challenges

Since Somalia's civil war erupted in 1991, the country

has mostly been without a central government. That makes

teaching American government that much more challenging.

The task falls upon Naima Hashi, 23, who has taught the

SDC's citizenship course since September. Hashi, who

everyone has called Nimo for as long as she can remember, is

also a refugee, and knows the challenges well.

Her family fled the war in 1991 for Addis Ababa, where

Hashi, the seventh of nine children, graduated from high

school. She was 18 when she came to America, but still had

to complete one year of high school to be eligible to apply

to college. She enrolled in Boston English, and recalls her

first year as "difficult."

"I was homesick. It was a different environment," she

said. "I didn't know anybody. I just wanted to get it done."

Hashi finished high school in 2002, went to Newbury

College for a two-year degree, and then transferred to the

University of Massachusetts at Boston, where she majors in

early childhood psychology. She graduates this spring and

hopes to work at the SDC full time.

"I was given the opportunity to do this, and I love to do

this," Hashi said. "I want to help people do something with

their opportunity. Sometimes I think what it would have been

like if I didn't get the opportunity to be a student. If I

can offer my help to those who need help, I would be happy."

Hashi acknowledged that coming from a family that

emphasized education helped her establish herself quickly in

the United States, and credits her father, who took two

years of night classes at Cambridge College to earn a

medical translation degree and today translates at local

hospitals for Somali and Ethiopian patients, for setting an

example.

Cultural adjustment

Not everyone responds so enthusiastically. Many Somalis

hope for peace and a return to Somalia without really trying

here. While most of the 10 to 20 students - almost all

females - who attend the citizenship classes seem to pay

attention to the lessons, a few others seem disinterested,

even resentful.

"Some people are just not up to new challenges, don't

want to try new things, wishing things were just easy and

handed to them," said Yusuf. "But the reality is many will

never go back. There lives are much better now, no matter

what they say."

For refugees struggling with culture shock and language

barriers, the Somali Development Center offers social

workers and teachers who speak their language and know their

culture, but help them acclimate to their new environment.

"We're not trying to Americanize them, but just give them

a view of how things here work," Hashi said.

Ahmed, the refugee widow, said the center helped her pass

her citizenship test and earn her citizenship on Nov. 8,

2006, a day she happily recalls. She reads and understands

English better than she speaks it, knows the different

branches of government, how checks and balances work, and

even ticks off the names of Supreme Court Justices like a

C-SPAN junkie. "If you can't change the past, you have to

work on the future," she said through a translator.

"I believe sometimes people don't know about small,

ethnic-based organizations like ours. They do 90 percent of

the work for these populations but get 10 percent of the

funds," said Yusuf. The center, he complains, could use more

workers but doesn't have the money to hire them. With

children of his own and overwhelmed with demands at he

center, Yusuf sometimes thinks about leaving. But then he

remembers how people like Ahmed got her citizenship and

stays put.

"I want to have an impact," he said. "I want to help

people become Somali Americans."

Source: Boston Globe

Daawo

Boston

webmaster@ceegaag.com |