|

Letters from Somalia: Risking

education

(Mogadishu, May

14,

2008 Ceegaag Online)

Despite the shelling and pitched battles in the Somali

capital, teachers, parents and students are willing to risk

life and limb for an education

In a

partly deserted neighborhood in the Somali capital - in

particular an area that has been the scene of recent and

frequent clashes between Somali government forces and

insurgents - stands a very ordinary house; a house that is,

despite the danger all around it, bustling with activity as

if it were existing in another, more peaceful world.

This house

is the Al-Khaliil Primary School, and the administrators,

teachers, parents and, above all, students are determined to

receive an education, whatever the cost.

Situated

in Harraryale in Mogadishu's Wardigley district, the school

hopes that its own courage will be the bulletproofing it

needs.

Abdurrahman Fodadde is the school principal and an old

friend of mine. He says that they have decided to continue

to educate the children who remained in the neighborhood

despite the constant flare-ups of violence.

"We cannot

wait to educate our children until peace comes to the

country because these people have waited long for it,"

Foodadde says. "I, together with the parents of the children

and the teachers, have met and agreed that we should

continue the education despite what is going on."

Somalia's

educational system has all but collapsed since the overthrow

of the late Somali ruler Mohamed Siyad Barre. Government

school buildings have either been destroyed by civil

conflict or settled by landless squatters. Some have even

been turned into waste dumps.

The recent

18-month conflict in Somalia, particularly in Mogadishu, has

led to the closure of most of the dozens of remaining

schools as nearly 70 percent of the residents have fled

their homes, according to projections provided by local and

international organizations.

But few

schools in the capital have remained opened to cater to the

educational needs of the children whose families opted to

stay behind. Al-Khaliil Primary is one of them.

When I

visited the school this week, both teachers and students

were preparing for final exams.

"We teach

when it is quite stable in the neighborhood and we close

when things are not that peaceful," says Foodadde.

"Fortunately none of the students has been hurt inside the

school, but some have had injuries outside school or at

their homes."

That, says

the principal, shows that we need to continue educating the

children because they are in just as much danger if they

stay at home.

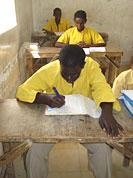

The

students were also committed to learning despite the danger.

In a

half-empty classroom, the students attentively follow their

teacher's lecture as he reviews with them the subjects they

have covered during the year in preparation for final exams

next week.

"I am

trying my best to study. I want to be a doctor and cure

people of diseases," Ahmed Dahir, in the fifth grade, says,

proudly displaying the high marks on his homework.

For many

families in the capital, educating their children has become

almost as much of a priority as keeping them safe amid

conflict.

For the

children of displaced families, makeshift schools were the

next thing - after a basic shelter - that people built for

their children to receive a semblance of education.

Fodadde

believes that if people do not continue to seek education

for their children even in this time of social upheaval the

country will never have a better prospect for stability

"As life

has always to be, we have to make the next generation better

than the one we now have or else there will be no future for

this country," Fodadde says.

Many here

seem to have a sense of what Fodadde is saying, and they

have set their priorities accordingly. So you will not be

surprised to see here young school children dashing about

for safety in the streets in the event of a shootout or an

all out confrontation between the warring sides.

Ordinary

people help these children who often go to schools a bit far

from home, and local authorities exempt the few existing

school buses from the street closures in the capital.

Foodadde

says that they have told parents and students that there are

times when they should not send the children to school and

that is when the fighting has already started before the

children have left their homes.

"On our

part we keep the students at the school in case fighting

starts while the children are there," the principal says.

"But if fighting breaks out, which usually lasts an hour at

the most, while students are en route, there is nothing we

can do but pray for their safety."

He said

that his school had a number of student causalities during

this school year, but that the students and teachers have

adapted to working in this exceptional circumstance.

"We have

no other choice but to keep on the light that will shine

into the darkness of our society."

Abdurrahman Warsameh is an ISN Security Watch correspondent

based in Mogadishu.

webmaster@ceegaag.com |